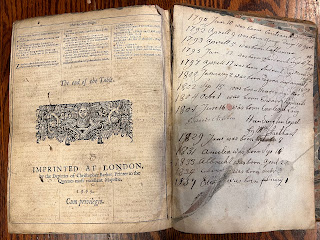

This is an original "1599 imprinted at London by the deputies of Christopher Barker” Geneva Bible. In spite of the preceding printer’s statement on the title page - and this is where it gets interesting - this Geneva Bible was actually printed in Amsterdam (in English, of course) around the year 1633, probably by J.F. Stam (John Fredericksz Stam) and Thomas Craffurt (a.ka. “Crafoorth”; 473 in Herbert*).

This is one of the “Puritanical printings” without the Apocrypha. Some of the so-called “Puritanical printings” of the Geneva Bible (for Puritans in the low countries), began to omit the Apocrypha, while other editions retained them. The Geneva Bibles were printed without the Apocrypha in a covert arrangement with the partners and heirs (“deputies”) of Christopher Barker, who died in 1599.

It is a singular fact of the bibliographic record that Geneva Bibles published in the region of the Netherlands in the 17th century, bore the date “1599” and gave the place of publication as “London.” These printings are what the uninitiated term “black market editions” (unless the edition is a Herbert 247, one of the very few "Imprinted at London...1599" that actually were published in that time and place).

1599 is the year that “pirated” Bibles attributed to Christopher Barker's deputies in London, were first printed in Amsterdam for expatriate Puritans. The 1599 date would be affixed to Geneva Bibles published in Amsterdam as late as the 1640s.

I have qualified the terms “black market” and “pirated” in the preceding references to this traffic, because in my opinion this was officially sponsored pseudo-piracy; likely a false flag operation made possible by the pact between Dutch printers and the Crown's royal printing company in London (“the deputies of Christopher Barker”), whose mission it was to keep the fact of royal sponsorship of a Bible suddenly appearing without fourteen of its books (Apocrypha), unknown to the world at large. The title page reads: “Imprinted at London by the Deputies of Christopher Barker, 1599.” In fact, it was not, as noted above.

Dodd's Own Bible?

Rarity: Besides its age, the provenance of this Bible makes it rare, as does the fact that may have been owned by William Dodd. The first page of the Bible is signed: Rev'd. Dr. Dodd.

Our search of 18th century British biography revealed only one cleric by that name. Here is his biography:

On June 27, 1777, the Reverend William Dodd (born 1729), “the Macaroni Parson,” Master of Arts and Doctor of Laws in the University of Cambridge; first Grand Chaplain of Modern English Freemasonry and sometime chaplain to King George III; Chaplain of Magdalen House, a “Public Place of Reception for Penitent Prostitutes”; proprietor of the Charlotte Street Chapel, and a principal sponsor of such other charities as the Society for the Release of Debtor, was hanged at Tyburn for forging the signature of his patron and former pupil, Philip Stanhope, fifth earl of Chesterfield, on a bond for £4,200.

Dodd's trial, condemnation, and execution occurred despite massive efforts to procure a mitigation of the law's severity led by his friend, the literary giant Samuel Johnson.

Dodd was the author of The Beauties of Shakespeare (1752). "This was the first and probably most influential of all Shakespearian anthologies, Lamb's Tales included. In its numerous subsequent editions, deluxe...and otherwise, it quickly became and remained a best-seller on both sides of the Atlantic...its conveniently arranged passages, arranged under such archetypes as "Hope," "Repentance," "Honor more Dear than Life," or "Punctuality in Bargains," probably did more than any other single agent to establish the actual parameters of the conventional Shakespearian canon and make it 'part of an Englishman's constitution.'

"Dodd indeed moved in Wilkite circles, and like (the radical) John Wilkes, he was drawn to Freemasonry, of which he became an enthusiastic advocate. Just over a year before his execution, and shortly before his troubles began, he had preached as Grand Chaplain of the Lodge of All England at the inauguration of the new Freemason's Hall in Long Acre, which was dedicated on May 23, 1776, with musical solemnities and oratorical pageantry on a scale which foreshadowed the great Handel commemoration of 1784 in Westminster Abbey.

"Dodd was a masonic enthusiast and publicist who occupied a position of Grand rank explicitly created to mark the dedication of the order's first permanent headquarters....Besides the simple fact that Dodd and Freemasonry seemed so made for each other that they were bound to rise or fall together, however, there were other circumstances which complicated the link between their fortunes...

"Dodd's execution was widely regarded, not as the condign exemplary punishment of a scoundrel but as the unmerited suffering of a victim more sinned against than sinning who had been heartlessly sacrificed to the letter, not the spirit, of the law after a trial which turned on a confession obtained by trickery and on evidence obtained by highly improper means.

"In severe financial difficulty after years of raising cash on annuities, Dodd had induced Lewis Robertson, a broker, to procure funds on Chesterfield's purported bond by posing as the earl’s confidential agent. Robertson had negotiated with a Mr. Fletcher in the bank of Sir Charles Raymond. Fletcher and another partner signed on behalf of the bank. Robertson had doubts. Anxious not to lose his commission, however, he eventually countersigned when Dodd hinted that further enquiry would offend the earl and end the transaction. A blot on the bond, however, caused Fletcher's solicitor Manly, to get it re-executed by the earl. This gave the game away.

"Confronted by Manly, Dodd confessed, protesting that he had always intended to repay as soon as his temporary difficulties were over and before the earl even knew. He denied any intention to defraud, declared Robertson's innocence, repaid most of the bond at once gave security for the balance. He passed up an opportunity to burn the evidence when Manly left him alone with it. Assured that the matter would be laid to rest, he also let Manly leave his house with the incriminating paper still intact.

"The following day, Manly swore an information for forgery before Sir Thomas Hallifax, the Lord Mayor and a prominent anti-Wilkite. Robertson was also charged as accomplice. To begin with, Chesterfield was reluctant to prosecute but he bowed to the arguments of Hallifax and Manly, who was anxious that his own client, Fletcher, should not bear the cost alone. A joint prosecution by Chesterfield and Fletcher was therefore entered. Neither showed much enthusiasm, however, and though newspaper speculation pointed to Sir Charles Raymond as the real driving force behind the case, it seemed unlikely that it would ever come to trial.

"Previous forgery trials had indicated considerable public sympathy for defendants in such cases. Moreover the crucial prosecution witness, Robertson, could not give evidence since he had also been arrested and charged. The defense argument—that there had been no malicious intent, that the money had been returned and securities given, and that the bond, now legally "blank," was being improperly held, either by Hallifax or by Manly, seemed strong enough to persuade the Middlesex Grand Jury to dismiss the charge.

"All this was changed, however, by Manly, who improperly secured Robertson's release by means of a falsely procured pass, thereby enabling him to testify against Dodd before the Grand Jury and giving him little choice but to do so in order to clear his own name. Without actually doing anything himself, in fact, Robertson had "been turned" king's evidence, not by any court, but by a trick played on an unsuspecting jailer by the prosecution's solicitor. Dodd was committed, and the critical question of the admissability of Robertson's evidence was left to be determined at the trial itself.

"To most lay opinion it still seemed that natural justice was entirely on Dodd's side. He had meant no harm, only to "borrow" the money for a short time. He had confessed, had redeemed the bond at once, and had not destroyed it when an opportunity to do so presented itself, only to be thrown off his guard by the assurances of designing men. Robertson's evidence had been illegally obtained; previous cases had been thrown out for less, and rumors were now beginning to circulate about Robertson's complicity in a deep conspiracy with Fletcher and his fellow bankers to frame both Chesterfield and his tutor.

"...On the ground that whatever they had done about Robertson, the Grand Jury had found a true bill against Dodd, the trial proceeded... Dodd had acted according to the manners of the time, whose he came to epitomize. This was particularly so with regard to the use and abuse of credit....Not only was Dodd a debtor himself; more important, he was conspicuously interested in the general problem. He preached on it in his own chapels in Pimlico and Bloomsbury; he supported the Thatched House Society, the principal existing debtors' charity; in 1772, he founded his own Society for the Relief and Discharge of Persons Imprisoned for Small Debts. He even tried to float a scheme for "the Loan of Money without Interest to Industrious Tradesmen.'...his own relief organization, which later became the Discharged Prisoners' Aid Society, freed over 3,200 victims during its first five years.

"...In some respects, the image of Dodd, benevolent, all too human, and martyred by the rigor of the law and the manners of the age, coincided with this. True, he had, in a moment of weakness and need, misappropriated the name of his patron. But if a noble name still carried with it some residual expectations of Good Lordship toward those who wore its livery, it might be plausibly argued borrowing was a venial breach of etiquette, not a premeditated crime, especially if noble patrons expected their inferiors to go on writing off their own notorious reluctance to pay their bills as a business. Besides, the merits of such a good and useful man should have been properly recognized and rewarded long before to such extremities."

Source: John Money, "The Masonic Moment; Or, Ritual, Replica, and Credit: John Wilkes, the Macaroni Parson, and the Making of the Middle-Class Mind" in Journal of British Studies 32 (October 1993): pp. 358-395.

If we knew for a fact that this was the personal Bible of William Dodd and autographed by him we would be asking ten times the price we are asking now. However, without a handwriting expert to verify the signature, William Dodd's ownership and autograph remain unverified. Let the buyer beware: we make no claim that this was his Bible, or is that it bears his autograph.

This rare, approximately 380-year-old Geneva Bible is in good condition for its age. All pages are present though there are some defects (see photos below). It was rebound in leather at some point, my guess is in the 18th or early 19th century. There is quill-pen handwriting on blank endpages front and back, including the aforementioned Dodd signature (which appears to be in a different hand from the one that listed the registry of births in the back of the Bible) None of this handwriting appears on any page of the Bible text itself which we checked (we did turn over every leaf). Some of the margin notes along the edge of some pages were trimmed off during the rebinding. There is also a small hole about one inch in diameter on one page.

7 inches by 9 inches. 2 lbs. 11 ozs. (All weights and dimensions are approximate).

For price and ordering details please see here

Questions? E-mail: rarebooks14ATmac.com (substitute @ for AT in the preceding address). Please read the descriptive text above and view all the photos before asking a question. Thank you.

*Historical Catalogue of Principal Editions of The English Bible, 1525-1961 by A.S. Herbert (New York, 1968). This is the standard reference work.

Click on the photos to enlarge them. Please take the time to examine each carefully.

Leather back cover

Text block

Spine

Closeup of the tear on the leather of the front cover

IMPORTANT NOTE: Title page [above] -- this page photographed black on white on our cell phone camera, but it is actually age-tanned as are all the pages of this Bible. They all exhibit yellowing/browning from age, as seen in the next two photos, even when the photos look black and white.

No comments:

Post a Comment